Hey Chuguitos (li’l chuggers),

A few years ago I came across a series of articles that blew my mind so much so that I decided to make it a part of my doctoral research. For me, it started with reading two Nature articles titled “Afternoon rains more likely over drier soils” and “Frequency of Sahelian storm initiation enhanced over mesoscale soil-moisture patterns”, both published by respective teams led by Christopher Taylor at the UK Center for Hydrology and Ecology. The idea is simple (or is it?). Over certain regions of the world, such as Northern Africa, Southern Great Plains of the United States, Europe, even the Tibetan Plateau, and hopefully soon subtropical South America (courtesy of yours truly), it has been observed that more clouds initiate and more rain falls over soils that are drier than their surroundings. What do I mean by “soils that are drier than their surroundings” you ask? Here’s one way that it can look like -

|———|

1 Kilometer

Shoutout to Dr. Susana Roque-Malo for the graphics, courtesy of Convey Science and you should check out their awesome website (convey.science).

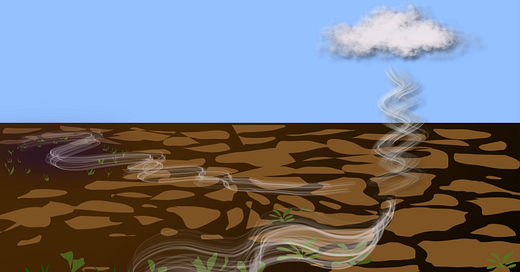

Imagine this above-depicted region of 50-100 km on each side (or 30-60 miles in real units) where the green bushes are absolutely not to scale. The soil in this region can be heterogeneously dry (light brown) based on how much water it can hold, or whether it rained in the vicinity the previous day, or if one part has a lush green vegetation cover and the other part doesn’t, etc. The bottom line is, when the soil is heterogeneously wet/dry, it will also heat up the air above it in a heterogeneous manner. When the sun comes out and the star go down, a drier surface gets heated up more than its surrounding wet surface, and in turn heats up the air right above it. The air in the vicinity, over the wetter patches (darker brown in the above illustration), doesn’t receive the same heating from below. And this, ladies and gentleman, is called a temperature gradient (break for applause!). Why is that important you ask? It is perhaps one of the most important concepts in fluid studies on our planet because all circulations, whether air in the atmosphere or water in the ocean, are driven by gradients of temperature.

This idea that heterogeneity or patchiness on the land surface can drive winds from wet (cooler) toward dry (hotter) regions has been around for a few decades (e.g. Segal and Arrit, 1992). When atmospheric modeling gathered steam in the second half of the twentieth century, their attempts to mathematically recreate the conditions in the atmosphere faced a lot of errors due to poor representation of conditions at the lower boundary of the model (i.e., the land surface). A plethora of land-atmosphere feedbacks were discovered in the subsequent years. This particular feedback where patchiness of the moist soil can induce its own wind was termed as ‘mesoscale circulations’ because the most common patchiness on the land surface arises due to non-uniform rainfall at the 50-100 km scale (this scale is termed as mesoscale in the atmospheric science community).

Patchy rain creates patchy soil which drives its own wind from wet (cold) to dry (hot) areas. So why does the title say “more clouds and rain”? This where things get interesting. Part of the reason that wind can blow horizontally toward the hot patch is that the air directly above the hot patch is hotter than its surroundings and hence, more buoyant. Buoyant air rises up, creating a void in its place that forces the cooler, moister winds from the vicinity to fill up the space. Hence, the horizontal flow is setup. Effectively, that hot patch has become a convergence zone where moist air from the vicinity rushes into horizontally and gets tossed up due to the heating from the dry soil. And what do we get when moist air rises? Cotton candies in the sky, duh!

This is not just ancient wisdom or the curse of our numerical models. We can actually see this happening from our satellites (that’s where I come in). Using satellite measurements of temperature and outgoing energy in our atmosphere, we can track every single cloud, small or big. We can also track where and when it is raining. In certain regions of the world, as described in the opening paragraph, we can see a clear preference for more frequent afternoon clouds and rainfall over drier patches of land as compared to the surrounding wetter regions at the mesoscale!

What does this mean for our future and why should we be excited about this? Well, for one, it opens the door for a highly controlled and less risky method to modify local and regional climate! If more clouds and more rain naturally happen because a huge cropland is located next to a forest, or because a lush forest was cleared to create a city, it means that theoretically we should be able to design land management techniques that can lead to desired outcomes in terms of changes in clouds and rainfall. Imagine an entire countries’ irrigation system timed perfectly to create patchiness such that it also irrigates the non-irrigated patches via the induced rainfall! Imagine cities staggered with green areas, located and designed in a way that keeps the sky more cloudy over the human settlement and thus keeps things cooler. Mesoscale heterogeneity at the land surface is an untapped engineering resource and its probably a more plausible and manageable technique than the ones that the writers of Geostorm invented. Shoutout to Gerard Butler; the movie sucked but you’re still the king!

I hope it blew your mind as much as it did mine. If you’re interested, do checkout those articles tagged above or email me if you want the full pdf (divyansh.chug@gmail.com). I’m off to a July Fourth barbeque so see you a couple thousand calories later. Until then, keeping chugging along y’all!